Cattle Drives, Cowboys & Cattle Towns

Western history of the 1870s and 1880s was primarily written in five states, including Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona. The first of the states was Texas, the starting point from which the turbulence and lawlessness subsequently prevailed in the states to the North and west of her boundaries. In Texas, the first cattle were assembled and later driven across the Chisholm and the lesser cattle trails towards the railroad junctions in the North. During this period, Kanas was the terminus point for most of these cattle driven from Texas. From these historical occurrences of the first cattle trails from Texas to Kansas, it could be said that the West was born in Texas and raised in Kansas.

Cattle Drives: The Days That Tried Men's Souls by Michael King

|

This book explores the early cattle trade, relives the challenges of a trail drive, describes the character of the cowboy, and retells the stories of individuals who endured the hardships of the cattle trails of the 1800s. The book provides interesting sketches of early cowboys and their experiences on the range and the trail during the days that tried men's souls. In addition, the book provides true narratives related to real CowPunchers and the men who fathered the cattle industry.

If the history of America's western frontier is the nation's narrative, then the cowboy must be its principal character. But, unfortunately, the cowboy is just as formidable to portray as the frontier itself. Contemporary accounts of so-called cowboys offer a modern historian no help determining the mysterious creatures. Some claim they were mischief makers. Others believed that cowboys were misconceived and misrepresented gentlemen. |

The Quirt and the Spur, by Edgar Rye

Far out beyond the confines of civilization, far out where daring men took possession of the hunting ground of the Indians and killed herds of buffalo to make a small profit in pelts, leaving the carcass to putrefy and the bones to bleach on the prairies. Far out where cattlemen disputed over the possession of mavericks, and the branding iron was the only evidence of ownership. Far out where a cool head backed the deadly six-shooter and the man behind the gun, with a steady aim and a quick trigger, won out in the game where life was staked upon the issue. Far out, where the distant landscape melted into the blue horizon, and a beautiful mirage was painted on the skyline. Far out where the weary, thirsty traveler camped overnight near a deep water hole, while nearby in the green valley, a herd of wild horses grazed unrestrained by man’s authority.

Far out where the coyote wolves yelped in unison as they chased a jackrabbit in a circle of death, then fought over his remains in a bloody feast. Far out where the gray Lobo wolf and the mountain lion stalked their prey, killed and gorged their fill until the light in the east warned them to seek cover in their mountain lairs.

Far out where bands of red warriors raided the lonely ranch house, killing, burning, and pillaging, leaving a trail of blood and ashes behind them as a sad warning to the white man to beware of the Indian's revenge.

Far out into this wonderful country of great possibilities, where the sun looked down upon a scene of rare beauty.

Far out where bands of red warriors raided the lonely ranch house, killing, burning, and pillaging, leaving a trail of blood and ashes behind them as a sad warning to the white man to beware of the Indian's revenge.

Far out into this wonderful country of great possibilities, where the sun looked down upon a scene of rare beauty.

The Texas Longhorn

The characteristics of the longhorn are of spectacular color, with shadings and combinations so varied that no two are alike. They reach maximum weight in eight or ten years and range from 800 to 1500 pounds. Although slow to mature, their reproductive period is twice as long as that of other breeds. Most longhorn cows and bulls have horns of four feet or less. However, mature steers have an average span of six feet or more, and a 15-year-old's horn span reaches up to nine feet. J Frank Dobie thus pictured a herd of Texas Longhorns:

|

Tall, bony, coarse-headed, coarse-haired, flat-sided, thin-flanked, some of them grotesquely narrow-hipped, some with bodies so long that their backs swayed, big ears cawed into out outlandish designs, dewlaps hanging and swinging in rhythm with their energetic steps, their motley-colored sides as bold with brands as a relief map of the Grand Canyon--mightily antlered, wild-eyed, this herd of full-grown Texas steers might appear to a stranger seeing them for the first time as a parody of their kind. But however they appeared, with their steel hoofs, their long legs, their stag-like muscles, their thick skins, their powerful horns, they could climb the highest mountains, swim the widest rivers, fight off the fiercest bands of wolves, endure hunger, cold, thirst and punishment as few beasts of the earth have ever shown themselves capable of enduring.

|

|

On the prairies, they could run like antelopes; in the thickets of thorn and tangle, they could break their way with the agility of panthers. They could rustle in drought or snow, smell out pasturage leagues away, live--without talking about the matter-like true captives of their own souls and bodies.

PART ONE:

The Texas Longhorn: The Remarkable Tale of Evolution and Economic Impact in Post-Civil War Texas

Journey back to the late 1400s and trace the remarkable history of the Texas Longhorn. These hardy, long-legged, long-horned creatures were born out of the accidental crossbreeding between escaped descendants of Creolo cattle, brought by Spanish explorers, and the cows of early American settlers. The Texas Longhorn represents a fascinating tale of evolution, adaptability, and economic impact.

Spanish explorers introduced their wiry, thin-legged, moorish, and Andalusian cattle to the Caribbean islands. When left to their own devices, the cattle grew prominent and turned wild. As Spanish explorers ventured further north, their exhausted cows were left loose on the trail. These cattle soon interbred with the cows of early American settlers, producing the hardy Texas Longhorn. These creatures are known for their long legs, long horns, defensive capabilities, and impressive adaptability.

Following the Texas Revolution, the Texas Longhorn had a significant influence on the state's economic prosperity. The revolution led to a change in governmental control, and many cattle were left to roam free in sparsely populated ranch land. The abundance of food, water, and little human contact allowed the Longhorn breed to adapt and flourish, with the cattle population growing into millions.

Spanish explorers introduced their wiry, thin-legged, moorish, and Andalusian cattle to the Caribbean islands. When left to their own devices, the cattle grew prominent and turned wild. As Spanish explorers ventured further north, their exhausted cows were left loose on the trail. These cattle soon interbred with the cows of early American settlers, producing the hardy Texas Longhorn. These creatures are known for their long legs, long horns, defensive capabilities, and impressive adaptability.

Following the Texas Revolution, the Texas Longhorn had a significant influence on the state's economic prosperity. The revolution led to a change in governmental control, and many cattle were left to roam free in sparsely populated ranch land. The abundance of food, water, and little human contact allowed the Longhorn breed to adapt and flourish, with the cattle population growing into millions.

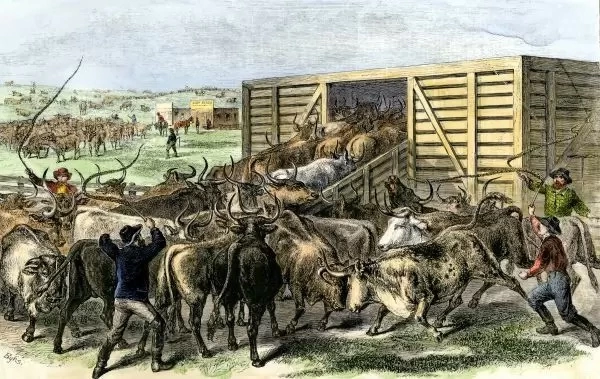

Cattlemen faced numerous challenges in marketing their herds due to Texas fever, a tick-borne disease that often sickened or killed local stock. However, the growth of the cattle population in Texas and the arrival of the Kansas-specific railroad opened up a northern market for Texas. This development marked a significant turning point in the economic prosperity of the state, driven by the abundance of Texas Longhorns.

The Texas Longhorn breed is characterized by its hardiness, intelligence, and adaptability. These characteristics allowed them to survive in harsh conditions and thrive in the wilds of the American Southwest. The Longhorn's ability to gain weight quickly and efficiently, even on meager resources, makes them a valuable asset for ranchers. Furthermore, their meat, particularly the roasts and ground beef, are renowned for their superior quality and taste.

Despite their wild origins, Texas Longhorns can be quite gentle and friendly, particularly once they trust their human caretakers. Their intelligence and alertness make them easy to work with, and their stunning array of patterns and colors adds to their appeal.

In conclusion, the Texas Longhorn is not just a breed of cattle; it is a symbol of Texas heritage and a testament to the resilience and adaptability of nature. Its impact on the state's economy post-Texas Revolution cannot be overstated, and its legacy continues to shape the economic landscape of the state. The tale of the Texas Longhorn, from its humble beginnings to its substantial economic impact, is indeed a fascinating journey through Texas history.

The Texas Longhorn breed is characterized by its hardiness, intelligence, and adaptability. These characteristics allowed them to survive in harsh conditions and thrive in the wilds of the American Southwest. The Longhorn's ability to gain weight quickly and efficiently, even on meager resources, makes them a valuable asset for ranchers. Furthermore, their meat, particularly the roasts and ground beef, are renowned for their superior quality and taste.

Despite their wild origins, Texas Longhorns can be quite gentle and friendly, particularly once they trust their human caretakers. Their intelligence and alertness make them easy to work with, and their stunning array of patterns and colors adds to their appeal.

In conclusion, the Texas Longhorn is not just a breed of cattle; it is a symbol of Texas heritage and a testament to the resilience and adaptability of nature. Its impact on the state's economy post-Texas Revolution cannot be overstated, and its legacy continues to shape the economic landscape of the state. The tale of the Texas Longhorn, from its humble beginnings to its substantial economic impact, is indeed a fascinating journey through Texas history.

Joseph G. McCoy & the Early Cattle Industry

|

Joseph McCoy was born December 21, 1837, in Sangamon County, Illinois, to David and Mary (Kirkpatrick) McCoy. McCoy spent a couple of years at Knox College in Galesburg. He married Sarah Epler on October 22, 1861. They had five children. In 1861 McCoy began to work in the mule and cattle industry. At the close of the Civil War, McCoy expanded his enterprise by buying animals in large quantities and shipping them to major livestock centers. After expanding his business to shipping large herds of cattle to slaughter, he quickly recognized flaws in the system. An average of longhorns in Texas caused their value to be only three to four dollars a head. In cities like Chicago, they were worth $30 to $40 a head. McCoy began to develop a transportation system that would send cattle north to more profitable markets. In 1867, he joined a firm that shipped as many as a thousand cattle a week.

|

In 1867 an Illinois cattle shipper named Joseph G. McCoy arrived upon a plan to revitalize the cattle industry. This young man conceived the idea of opening an outlet for Texan cattle. Being impressed with the knowledge of the number of cattle in Texas and the difficulties of getting them to market by the routes and means then in use, and realizing the significant disparity between Texas values and Northern prices of cattle, he set himself to thinking and studying to hit upon some plan whereby these great extremes would be equalized. The goal was to establish at some accessible point a depot or market to which a Texan drover could bring his stock unmolested, and there, failing to find a buyer, he could go upon the public highways to any market in the country he wished. In short, it was to establish a market at which the Southern drover and Northern buyer would meet upon an equal footing and both be undisturbed by mobs or swindling thieves... Wild West Podcast presents Cattle Drives, Cowboys, and Cattle Towns: Part 2 Joseph G. McCoy and the Cattle Industry of the 1800s. Stay with us after this episode as we explore the plausibility of the cattle trade and ask the question, what would have happened to the westward expansion if the cattle trade industry had never existed?

"All over the land are vast and handsome pastures, with good grass for cattle . . .” A grass that moved as a heaven-weaved quilt of the earth, as if by root and stem, stood in protection of a hardy breed of livestock known as the Longhorn. Wild West Podcast proudly presents Trails, Cattle Drives, Cowboys, and Cattle Towns, Part 1: The Longhorn. Please join us at the end of the podcast as we review some interesting facts about the characteristics of the longhorn.

PART TWO:

Joseph McCoy's Legacy: Transforming the Cattle Industry and Reshaping the Course of Western Expansion

|

Prepare to step back in time as we embark on a captivating journey into the world of 19th-century cattle industry. Our focus for this fascinating exploration is none other than Joseph G McCoy, a visionary whose contributions fundamentally altered the cattle trade, transforming the face of Western Expansion in the process.

In the heart of Abilene, Kansas, a remarkable transformation took place. The birth of the first cow town was a spectacle to behold, complete with a pen capable of housing a thousand head of cattle, a hotel, a bank office, and a livery stable. The mastermind behind this impressive feat? Joseph G McCoy. McCoy's innovative ideas and ambitious vision led to the establishment of this flourishing cow town and paved the way for a booming cattle trade industry. However, the influence of McCoy extended beyond the realm of the cattle industry. His work was instrumental in shaping the broader historical era of Western Expansion. The revitalization of the cattle industry under his watch led to the establishment of numerous stock ranges and played a pivotal role in bridging the north-south divide that had persisted following the Civil War. |

McCoy's efforts in the cattle industry were nothing short of transformative. He perceived the considerable disparities in cattle values between Texas and northern states and sought to establish a depot where the Southern Drove and Northern Buyer could meet on equal terms. His ambition resulted in a unique transportation system that brought Texas cattle to the market, greatly impacting the mid-continent regions.

Joseph G McCoy's influence reached far beyond the cattle industry. His contributions were pivotal in shaping the Western Expansion and played a significant role in healing the animosity between northern and southern states, which had been created by the abolition movement in the Civil War. This episode prompts us to imagine what the West would have looked like if McCoy had not played his part in history.

McCoy's vision did not only stimulate the cattle industry but also ignited a period of unprecedented growth in Western America. The cattle trade, driven by the establishment of McCoy's cow town, catalyzed the development of new homes, farms, schools, and communities. It is a testament to McCoy's foresight and innovative thinking that the Western expansion was accelerated, paving the way for a period of prosperity and progress.

As we journey through this captivating historical era, we can't help but appreciate the immense impact of Joseph G McCoy on the cattle industry and Western Expansion. His legacy remains etched in the annals of American history, a testament to his visionary leadership and transformative contributions. His work serves as a poignant reminder of the power of innovation and the indomitable spirit of human resilience and ingenuity.

Joseph G McCoy's influence reached far beyond the cattle industry. His contributions were pivotal in shaping the Western Expansion and played a significant role in healing the animosity between northern and southern states, which had been created by the abolition movement in the Civil War. This episode prompts us to imagine what the West would have looked like if McCoy had not played his part in history.

McCoy's vision did not only stimulate the cattle industry but also ignited a period of unprecedented growth in Western America. The cattle trade, driven by the establishment of McCoy's cow town, catalyzed the development of new homes, farms, schools, and communities. It is a testament to McCoy's foresight and innovative thinking that the Western expansion was accelerated, paving the way for a period of prosperity and progress.

As we journey through this captivating historical era, we can't help but appreciate the immense impact of Joseph G McCoy on the cattle industry and Western Expansion. His legacy remains etched in the annals of American history, a testament to his visionary leadership and transformative contributions. His work serves as a poignant reminder of the power of innovation and the indomitable spirit of human resilience and ingenuity.

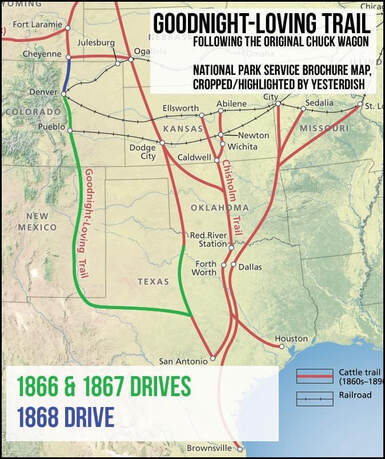

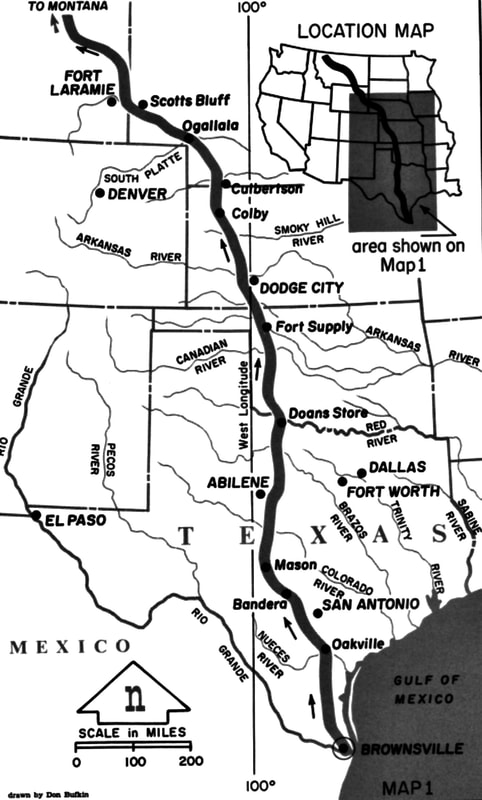

Cattle Trails

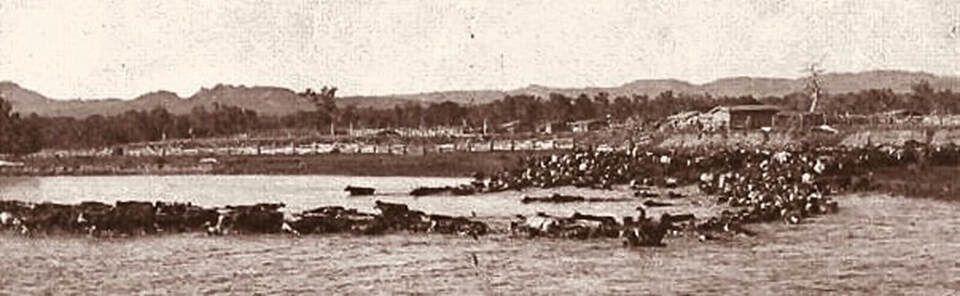

When the first herds were taken north in the early l840s, they reversed the trek, opening a trail to the railheads in Missouri. Newspapers referred to the route as the Sedalia Trail or the cattle trail. No one knows why it was called the Shawnee Trail; however, the route passed by a Shawnee village in north Texas near the Shawnee Hills in Indian Territory. By the late l850s, the name was in general use. In the 1840s, during the Mexican War, the trail was used almost constantly during the summer months. The gold rush in California increased demand for cattle after l848, and the Shawnee Trail was heavily used for several years. By the mid-1850s, Kansas City, Missouri, was the largest stock market in the west, and the Texas cattle trailing industry was well established.

The Shawnee Trail was the first major route used by the cattle trailing industry to deliver longhorns to the markets of the Midwest. Longhorns were collected around San Antonio, Texas, and taken northward through Austin, Waco, and Dallas, crossing the Red River near Preston, Texas, at Rock Bluff. Here at the emanation of this point of the trail provided a place forming a natural chute that forced the cattle together at the ford, and a gradual rise on the north bank made it easy to exit the river. In fact, many drovers were killed at the very beginning of the drive at the Red River. There were four crossings: Rock Rock River Crossing, Red River Station, Doan's Crossing, and Ringgold. Andy Adams described Doan's Crossing:

|

|

"Red River, this boundary river on the northern border of Texas, was a terror to trail drivers. The majestic grandeur of the river was apparent on every hand, with its red bluff banks, the sediment of its red waters marking the timber along its course, while the driftwood, lodged in trees and high on the banks, indicated what might be expected when she became sportive or angry.

The crossing had been in use only a year or two when we forded, yet five graves, one of which was less than ten days made, attested her disregard for human life. It can safely be asserted that at this and lower trail crossings on Red River, the lives of more trail men were lost by drowning than on all other rivers together.” |

|

C. H. Rust of San Angelo, Texas, stated in an article written for the book, The Trail Drivers of Texas by J. Marvin Hunter that he thought the Chisholm Trail started at San Antonio, to Abilene, Kansas; a distance of about 650 miles.

"The old Chisholm Trail started at San Antonio and ended at Abilene, Kansas. From San Antonio, it went to New Braunfels, then to San Marcos, crossing the San Marcos River about four miles below town, then to Austin, crossing the Colorado River about three miles below Austin. Leaving Austin, the trail wound its way on to the right of Round Rock, thence, to the right of Georgetown, to the right of Belton, to old Fort Graham, crossing the Brazos River to the left of Cleburne, then to Fort Worth, winding its way to the right of Fort Worth, crossing the Trinity River just below town. From Fort Worth, the next town was Elizabeth, and from there to Bolivar; here, the old Trail forked, but the main trail went up to St. Jo and north to Red River Station." |

From 1867 to 1889, the two most prominent cattle trails in Texas were the Western Trail, also known as the Fort Griffin-Dodge City Trail, and the Eastern Trail, also known as the Chisholm Trail. To confuse matters further, the Chisholm Trail has also been historically referred to as the Abilene, Caldwell, Cattle, Great Texas Cattle, Kansas, and McCoy's Trail. Still, Texas historians acknowledge that the names of these trails do not resonate as loudly within American history or attract as much tourism as Chisholm Trail. To follow the history of the cattle trails, Joseph G. McCoy, a businessman, and entrepreneur, is credited with the extension of the trail as far south as Brownsville, Texas, which became known as the Chisholm trail. The first cattle trail was named after Jesse Chisholm, a Scotch-Cherokee fur trader who forged a route from Wichita, Kansas, to the North Canadian River. The Chisholm Trail became popularized in American history through songs, stories, mythical tales, radio, television, and movies. To this day, historians and enthusiasts debate various aspects of the Chisholm Trail's history, especially the route and name. Wild West Podcast proudly presents Cattle Trails and the Men who Founded Them. Stay with us after this episode as Mike and I explore; Why historians continue to debate the true names of the early trials.

PART THREE:

Echoes from the Past: The Tales and Turmoil of America's Cattle Trails

|

In the 19th century, the American West was marked by the dust and echoes of cattle trails. These trails, which stretched across vast landscapes, were the lifelines of the cattle industry and played a crucial role in shaping America's history. This blog post delves into the fascinating tales of these trails, uncovering the characters, controversies, and significance that still resonate today.

From 1867 to 1889, the two most prominent cattle trails were the Western and Eastern Trails, with the latter also known as the Chisholm Trail. These trails were named after the Scotch-Cherokee fur trader, Jesse Chisholm, who established a route from Wichita, Kansas, to the North Canadian River. |

|

Over time, these trails have been etched into American history through songs, stories, and movies. Yet, historians continue to debate the true names and routes of these early trails, a reflection of the complexities and mysteries surrounding their history.

A significant character in the narrative of these cattle trails is Joseph G McCoy, an Illinois entrepreneur who revolutionized the cattle industry. McCoy opened up an outlet for Texas cattle in 1867, extending the Chisholm Trail as far south as Brownsville, Texas. This strategic move fueled the growth of the cattle industry, bringing an influx of settlers, increasing resistance against cattle drives, and intensifying the controversies around these trails.

Cattle drives were the backbone of the cattle industry during this era, bringing a steady flow of cattle from the South to the North. The most famous of these drives was the Chisholm Trail, which ran from San Antonio to Abilene, Kansas. The trail played a crucial role in the settlement of the West and had a profound impact on the landscape of the American West. However, this period was also marked by conflict, with violence often erupting between drovers and blockades, particularly during the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

In the latter part of this historical era, the Western Trail and the Great Western Cattle Trail emerged as the two main routes for exporting cattle from Texas. These trails carried not only cattle but also stories and legends, etching their paths into the landscape and history of the American West. The Western Trail, in particular, was steeped in controversy over its naming and the placement of markers along the route.

As the cattle trails receded into history, they left behind a landscape shaped by the hooves of countless cattle and the grit of the men who drove them. The tales of these trails continue to echo through time, offering a glimpse into a pivotal era in America's history. Through the dust and echoes, the stories of the cattle trails remind us of the rugged spirit and relentless drive that shaped the American West.

The exploration of these cattle trails not only uncovers the past but also provides insights into the present. As we trace the paths of our ancestors, we gain a deeper understanding of the forces that have shaped our nation. Whether it's the turbulent history of the cattle drives or the echoes of the Chisholm Trail, these tales offer a rich tapestry of America's past, inviting us to saddle up and journey into the heart of our nation's history.

Cattle drives were the backbone of the cattle industry during this era, bringing a steady flow of cattle from the South to the North. The most famous of these drives was the Chisholm Trail, which ran from San Antonio to Abilene, Kansas. The trail played a crucial role in the settlement of the West and had a profound impact on the landscape of the American West. However, this period was also marked by conflict, with violence often erupting between drovers and blockades, particularly during the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

In the latter part of this historical era, the Western Trail and the Great Western Cattle Trail emerged as the two main routes for exporting cattle from Texas. These trails carried not only cattle but also stories and legends, etching their paths into the landscape and history of the American West. The Western Trail, in particular, was steeped in controversy over its naming and the placement of markers along the route.

As the cattle trails receded into history, they left behind a landscape shaped by the hooves of countless cattle and the grit of the men who drove them. The tales of these trails continue to echo through time, offering a glimpse into a pivotal era in America's history. Through the dust and echoes, the stories of the cattle trails remind us of the rugged spirit and relentless drive that shaped the American West.

The exploration of these cattle trails not only uncovers the past but also provides insights into the present. As we trace the paths of our ancestors, we gain a deeper understanding of the forces that have shaped our nation. Whether it's the turbulent history of the cattle drives or the echoes of the Chisholm Trail, these tales offer a rich tapestry of America's past, inviting us to saddle up and journey into the heart of our nation's history.

Cowboy Culture

|

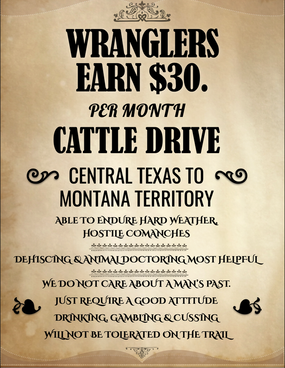

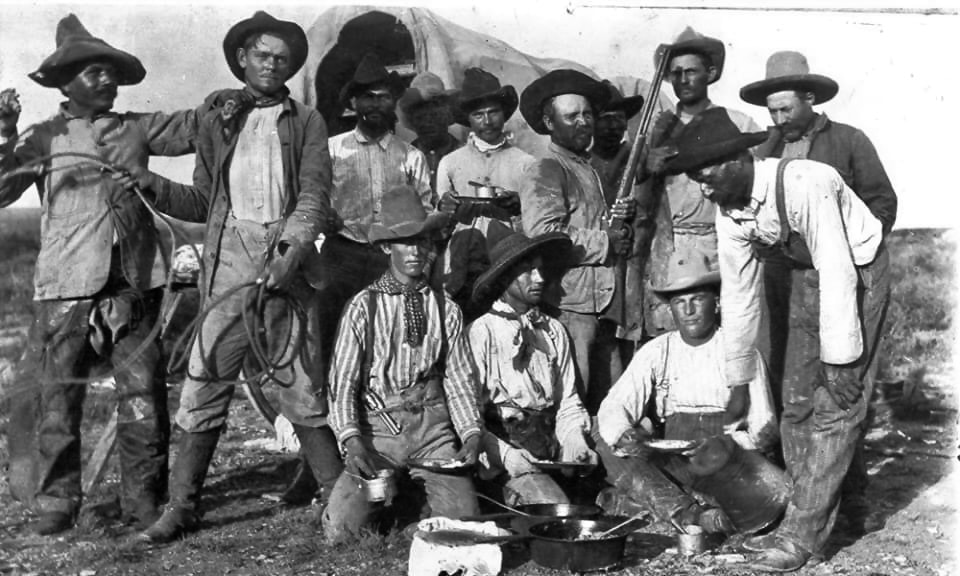

For twenty years, it was the ambition of every Texas cowboy to go up the trail. Wages were about $30.00 per month. Sometimes the cowboys were paid slightly more if they furnished their own horses. Trail life was hard. Cowboys usually had to work fifteen to eighteen hours a day; twenty-four hours if they had a bad night with restless cattle, and then they had to work the next day just as though they had slept all night. The trail boss took the position that they could sleep all next winter.

The men would even put tobacco in their eyes to stay awake. A cowhand never thought of trying to collect overtime or calling for shorter hours and more pay. In view of all of the hardships and dangers of trail life, why did they want to go up the trail? A cowboy did not feel that he had graduated in his art until he had made a northern drive. Many of them went year after year. From the end of the Civil War until the mid-1880s, tens of thousands of cowboys rode the cattle trails. Of course, not all cowhands made the trek northward, but as one Lockhart drover put it, a man did not graduate from cowboy school until he "lit out" on at least one long ride. |

PART FOUR:

Unraveling the Vaquero's Legacy: A Deeper Look at the American Cowboy Culture

The American cowboy is a central character in our nation's narrative, an iconic figure synonymous with grit, determination, and an unyielding spirit. This podcast episode takes listeners on an immersive journey into the heart of cowboy culture, stripping away romanticized myths to reveal the raw, often dangerous reality of this quintessential frontier figure.

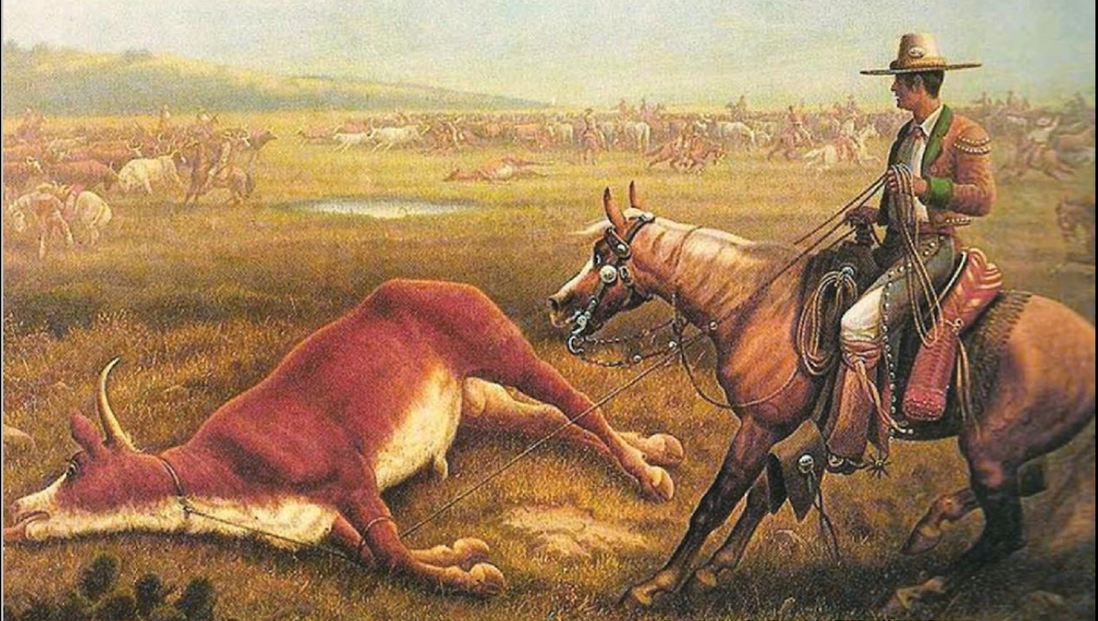

The influence of Mexican vaqueros on the American cowboy is undeniable. This cultural fusion of Spanish and Mexican roots has left an indelible mark on the cowboy persona, influencing everything from their practical attire to the deeply ingrained traditions of open-range ranching, branding, and roundups. As we peel back the layers of this cross-cultural heritage, we uncover how terms like "lasso", "lariat", "mustang", "chaps", and "bandana" became ingrained in our vernacular, and how these influences shaped the American cowboy we recognize today.

The life of a cowboy was far from the Hollywood glamor often depicted. It was a rugged, dangerous lifestyle, fraught with perils from weather, wild animals, and even human threats. Their attire, designed for practicality and protection, evolved over time into the iconic image we associate with cowboys. High-heeled boots, wide-brimmed hats, leather chaps, and revolvers were not just accessories, but necessary tools for survival in the harsh frontier.

The cowboy's day-to-day existence was filled with hard work and few rewards. However, their fierce loyalty to their outfits, their love for practical jokes, and their fondness for telling tall tales added color to their lives. Despite the hardships, there was a certain allure to the cowboy lifestyle, an irresistible pull towards the open range, the camaraderie of the trail, and the independence it offered.

The northern trail ride held particular importance for cowboys. This challenging journey symbolized their hard-working, independent spirit, a testament to their resilience and courage. Despite the grueling conditions, cowboys embraced this adventure with enthusiasm, viewing it as a rite of passage, a test of their mettle.

In conclusion, the American cowboy's rich and diverse heritage is a fascinating blend of cultures, traditions, and influences. This exploration provides a deeper understanding of the cowboy culture, revealing a far more complex and nuanced figure than the romanticized depictions we often see. The cowboy's story is an integral part of our nation's history, a testament to the enduring spirit of resilience, adaptability, and grit that defines the American frontier.

The influence of Mexican vaqueros on the American cowboy is undeniable. This cultural fusion of Spanish and Mexican roots has left an indelible mark on the cowboy persona, influencing everything from their practical attire to the deeply ingrained traditions of open-range ranching, branding, and roundups. As we peel back the layers of this cross-cultural heritage, we uncover how terms like "lasso", "lariat", "mustang", "chaps", and "bandana" became ingrained in our vernacular, and how these influences shaped the American cowboy we recognize today.

The life of a cowboy was far from the Hollywood glamor often depicted. It was a rugged, dangerous lifestyle, fraught with perils from weather, wild animals, and even human threats. Their attire, designed for practicality and protection, evolved over time into the iconic image we associate with cowboys. High-heeled boots, wide-brimmed hats, leather chaps, and revolvers were not just accessories, but necessary tools for survival in the harsh frontier.

The cowboy's day-to-day existence was filled with hard work and few rewards. However, their fierce loyalty to their outfits, their love for practical jokes, and their fondness for telling tall tales added color to their lives. Despite the hardships, there was a certain allure to the cowboy lifestyle, an irresistible pull towards the open range, the camaraderie of the trail, and the independence it offered.

The northern trail ride held particular importance for cowboys. This challenging journey symbolized their hard-working, independent spirit, a testament to their resilience and courage. Despite the grueling conditions, cowboys embraced this adventure with enthusiasm, viewing it as a rite of passage, a test of their mettle.

In conclusion, the American cowboy's rich and diverse heritage is a fascinating blend of cultures, traditions, and influences. This exploration provides a deeper understanding of the cowboy culture, revealing a far more complex and nuanced figure than the romanticized depictions we often see. The cowboy's story is an integral part of our nation's history, a testament to the enduring spirit of resilience, adaptability, and grit that defines the American frontier.

Cattle Drives

|

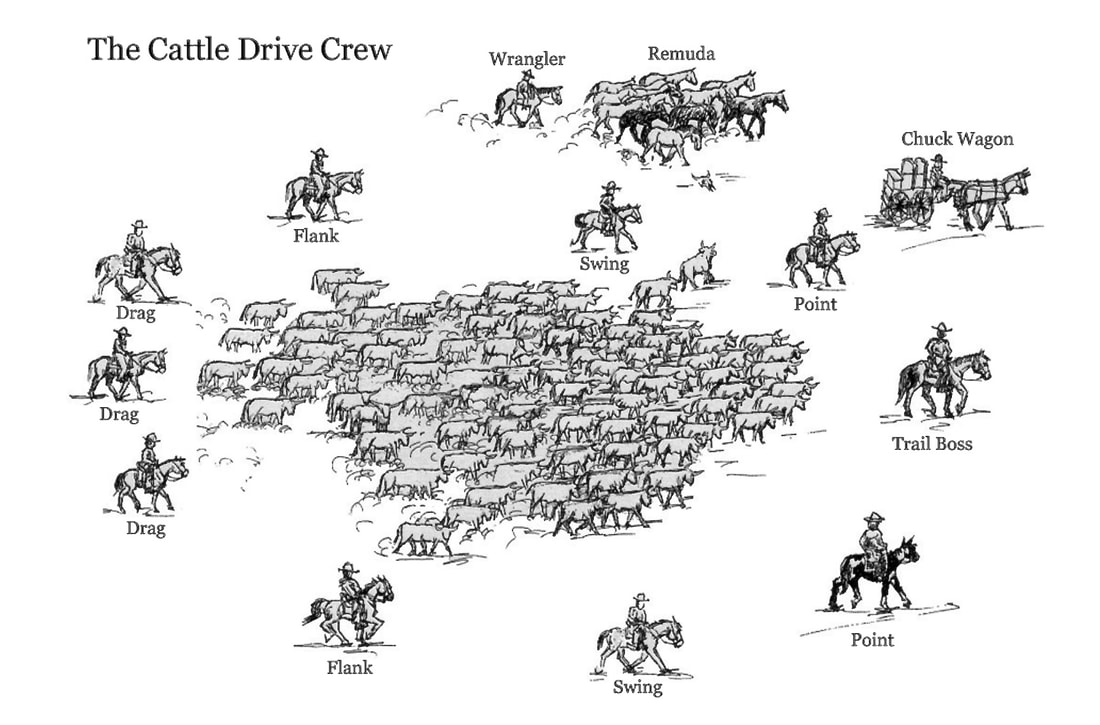

Cattle drives were led by a trail boss, whose job it was to hire the other cowboys for the drive, plan the route (making sure they would have sources of water), locate campsites, and lead his cattle north. One cowboy was hired for every 250 to 300 head of cattle; this meant that a typical herd of 2,000 to 3,000 longhorns would require eight to twelve cowboys. The cowboys looked after the animals on the trail, kept them moving along the trail, and tried to prevent them from breaking into a stampede. The cook, usually an older cowboy, often called the Old Lady, was one of the most important members of a cattle drive crew. A good cook kept the cowboys happy with good "grub," tended wounds, and took care of other domestic duties.

|

|

|

He was the second-highest-paid member of the crew behind the trail boss. The lowest-paid member of the crew was the wrangler, a younger cowboy who looked after the herd of workhorses. A herd on the trail moved about ten miles a day. Leading the way were the trail boss and the cook with his chuck wagon. To the side of the herd rode most of the cowboys, who kept wandering cattle from separating from the rest of the herd. Bringing up the rear, and eating the dust of several thousand shuffling cattle, were the drag men. Cowboys joked that the drag was where a cowboy learned to curse. Wild West Podcast proudly presents Cattle Drives, Cowboys, and Cattle Towns, Part 5: The Cattle Drive.

Each cowhand had specific duties. Several highly skilled cowhands, known as pointers, also called point rider or lead rider, rode at the side of the lead cattle to direct the herd. The point man who rides near the front of the herd determines the direction, controls the speed, and gives the cattle something to follow. Larger herds sometimes necessitate the use of two-point men. A privileged position on the drive, this job is reserved for more experienced hands who know the country through which they are traveling.

|

PART FIVE:

Saddle Up for Adventure: A Deep Dive into Cattle Drives and Cowboy Life in the Wild West

|

From cattle branding to the daily struggles of cowboys, the Wild West era was a time of incredible adventures and perilous journeys. Our latest podcast episode takes listeners on a deep dive into the life and dangers of cattle drives in the Wild West.

Cattle drives originated from the necessity of moving large herds of cattle to markets, often hundreds of miles away. Cowboys, using their unique skills and equipment, were the vital workforce that facilitated these drives. The roundup process, heavily influenced by Spanish practices, was an intricate dance of man and beast. Cattle were herded, branded to confirm ownership, and then separated into manageable herds. Each cowboy played a significant role, from the trail boss who navigated the route to the invaluable cook who kept the men fed. |

One might think that a cattle drive was a slow, mundane journey. On the contrary, it was an adrenaline-pumping adventure fraught with danger. Stampede was a constant threat, often triggered by thunderstorms, prairie dog holes, and sheer fatigue from the journey. The terrain could change dramatically, particularly when crossing the Red River into Indian Territory. Cowboys had to navigate encounters with wild animals and native tribes while also dealing with the looming threat of cattle rustlers.

As the drive moved north, the landscape presented its own set of challenges. A lack of timber made fires difficult to maintain, while prairie dog holes presented a danger to horses. Despite these hardships, many cowboys found pleasure in the camaraderie of life on the trail and the excitement of reaching town with pockets full of money.

However, this lifestyle was not without its physical and emotional tolls. Sleep deprivation was a significant hardship, as cowboys often had to stand night guard to prevent cattle from straying or stampeding. Many had to rub tobacco juice in their eyes just to stay awake. It was a hard, demanding life that required grit, resilience, and a deep love for the open prairie.

The Wild West era was a time of independence, danger, and adventure. Through our podcast, we aim to shed light on the lives of those who shaped this period of history, from the trail bosses to the dragmen. The stories, challenges, and victories of these individuals are a testament to the human spirit's resilience and the enduring allure of the Wild West.

The legacy of the Wild West continues to captivate audiences today. The iconic cowboy, the dangerous cattle drives, and the wild, open prairie all evoke a sense of adventure and freedom. As we delve into this history, we not only understand more about our past, but we also gain a deeper appreciation for the bravery and tenacity of those who lived through it.

In conclusion, the Wild West and the cattle drives were not just about cowboys and cattle. They were about courage, endurance, and the relentless pursuit of a better life. It's these qualities that continue to resonate with us today, making the Wild West an enduring part of our cultural heritage.

As the drive moved north, the landscape presented its own set of challenges. A lack of timber made fires difficult to maintain, while prairie dog holes presented a danger to horses. Despite these hardships, many cowboys found pleasure in the camaraderie of life on the trail and the excitement of reaching town with pockets full of money.

However, this lifestyle was not without its physical and emotional tolls. Sleep deprivation was a significant hardship, as cowboys often had to stand night guard to prevent cattle from straying or stampeding. Many had to rub tobacco juice in their eyes just to stay awake. It was a hard, demanding life that required grit, resilience, and a deep love for the open prairie.

The Wild West era was a time of independence, danger, and adventure. Through our podcast, we aim to shed light on the lives of those who shaped this period of history, from the trail bosses to the dragmen. The stories, challenges, and victories of these individuals are a testament to the human spirit's resilience and the enduring allure of the Wild West.

The legacy of the Wild West continues to captivate audiences today. The iconic cowboy, the dangerous cattle drives, and the wild, open prairie all evoke a sense of adventure and freedom. As we delve into this history, we not only understand more about our past, but we also gain a deeper appreciation for the bravery and tenacity of those who lived through it.

In conclusion, the Wild West and the cattle drives were not just about cowboys and cattle. They were about courage, endurance, and the relentless pursuit of a better life. It's these qualities that continue to resonate with us today, making the Wild West an enduring part of our cultural heritage.

The Chuck Wagon

|

|

At roundup time or on a five-month trail drive that covered 1500 miles, the chuck wagon was an essential piece of equipment in the cattle industry, and the cook was the most important person. More than any other man, the cook ensured the men were happy and productive. Without good food, men would quit, and the work would not get done. So it was well said among the cowboys before mealtime.

Feeding cowboys on long drives to northern cattle markets required planning and ingenuity. Early drovers usually packed food, bedding, and gear on horses or mules and had to cook for themselves. Their meager and monotonous fare consisted of biscuits or cornbread, salted or dried meat, occasional wild game, and coffee. |

|

Historians credit rancher and drover Charles Goodnight with inventing the chuck wagon in 1867. The first chuck wagon was used in 1867 on a trail drive from central Texas to New Mexico. Charles Goodnight purchased an army surplus ammunition wagon with iron axles and had the legs of a clerk’s writing desk. Travelers' portable writing desks and mess chests may have inspired Goodnight to attach a hinged wooden cupboard to a wagon for food preparation on the trail. When unfolded, the cover of this "chuck box" formed a working surface with access to shelves and drawers filled with staples, spices, utensils, and medicine. |

|

The Chuck Wagons' distinctive feature was the chuck box, a 4' x 3' box two to three feet deep located on the rear of the wagon. A board, hinged at the bottom of the box, folded down to form a work table. The box was divided into cubbyholes and drawers for small amounts of food, medicines, eating utensils, cooking equipment, tobacco, and perhaps whiskey. Elsewhere they tucked a Dutch oven, skillets, a water barrel, flour, horseshoeing equipment, branding irons, tools, and bedrolls: everything needed to care for the cowboys and keep them happy and working.

PART SIX:

From Cowboy Humor to Cattle Drive Logistics: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Chuck Wagon Era

Immerse yourself in the rugged landscape of the Old West as we explore the intriguing history and pivotal role of the Chuck Wagon in our latest podcast episode. The Chuck Wagon, an iconic symbol of the cowboy era, was more than just a mobile kitchen - it was the heart and soul of the cattle drive, a lifeline for the cowboys on the long trail, and a beacon of comfort and camaraderie amidst the harsh wilderness.

In the episode, we delve into the birth of the Chuck Wagon, which was invented by Charles Goodnight. This ingenious creation was a rolling pantry, a pharmacy, a bank, and a post office, all in one. Filled with staples, spices, utensils, and medicines, the Chuck Wagon was designed to cater to the cowboy's every need while on the move.

However, the real star of the show was the Chuck Wagon's cook. This key player was responsible not only for stoking the fires of the Chuck Wagon but also the morale of cowboys on the long trail. The cook, often a seasoned cowboy himself, held the daunting responsibility of feeding the crew three meals a day during the cattle drives. This crucial role earned him a high standing among the cowboys, who knew that a good meal was essential for their happiness and productivity on the trail.

The podcast also touches upon the lighter side of life on the trail, with a look at the practical jokes that kept spirits high around the Chuck Wagon. The cowboys, despite the harsh conditions and hard work, never lost their sense of humor, often finding amusement in the pranks and banter that took place around the Chuck Wagon.

Additionally, we also delve into the strategic logistics that went into planning and executing a successful cattle drive. The placement of the Chuck Wagon, the setting up of camp, and the careful navigation of the terrain were all key components of these drives. The cowboys were intimately familiar with the landscape, knowing exactly where to set up camp for the night and how to steer the herd to their destination.

Finally, we also touch upon the culinary side of the Chuck Wagon, with a look at some of the dishes served up by the cook. From the simple but hearty meals of biscuits or cornbread, salted or dried meat, and coffee, to more exotic concoctions like "spotted pup" and "shivering lizz," the Chuck Wagon's fare was as diverse and fascinating as the cowboys themselves.

This episode is a testament to the resilience, ingenuity, and camaraderie of the cowboys of the Old West. Through the Chuck Wagon, we get a glimpse of their daily lives, their challenges, and their triumphs. Whether you're a history buff, a cowboy enthusiast, or simply curious about the Old West, this podcast episode is sure to offer a unique and engaging insight into a bygone era that continues to captivate us today.

So, dust off your cowboy hats, pull on your boots, and join us as we embark on this exciting journey into the heart of the Old West, bringing to life the rich history and enduring legacy of the Chuck Wagon.

In the episode, we delve into the birth of the Chuck Wagon, which was invented by Charles Goodnight. This ingenious creation was a rolling pantry, a pharmacy, a bank, and a post office, all in one. Filled with staples, spices, utensils, and medicines, the Chuck Wagon was designed to cater to the cowboy's every need while on the move.

However, the real star of the show was the Chuck Wagon's cook. This key player was responsible not only for stoking the fires of the Chuck Wagon but also the morale of cowboys on the long trail. The cook, often a seasoned cowboy himself, held the daunting responsibility of feeding the crew three meals a day during the cattle drives. This crucial role earned him a high standing among the cowboys, who knew that a good meal was essential for their happiness and productivity on the trail.

The podcast also touches upon the lighter side of life on the trail, with a look at the practical jokes that kept spirits high around the Chuck Wagon. The cowboys, despite the harsh conditions and hard work, never lost their sense of humor, often finding amusement in the pranks and banter that took place around the Chuck Wagon.

Additionally, we also delve into the strategic logistics that went into planning and executing a successful cattle drive. The placement of the Chuck Wagon, the setting up of camp, and the careful navigation of the terrain were all key components of these drives. The cowboys were intimately familiar with the landscape, knowing exactly where to set up camp for the night and how to steer the herd to their destination.

Finally, we also touch upon the culinary side of the Chuck Wagon, with a look at some of the dishes served up by the cook. From the simple but hearty meals of biscuits or cornbread, salted or dried meat, and coffee, to more exotic concoctions like "spotted pup" and "shivering lizz," the Chuck Wagon's fare was as diverse and fascinating as the cowboys themselves.

This episode is a testament to the resilience, ingenuity, and camaraderie of the cowboys of the Old West. Through the Chuck Wagon, we get a glimpse of their daily lives, their challenges, and their triumphs. Whether you're a history buff, a cowboy enthusiast, or simply curious about the Old West, this podcast episode is sure to offer a unique and engaging insight into a bygone era that continues to captivate us today.

So, dust off your cowboy hats, pull on your boots, and join us as we embark on this exciting journey into the heart of the Old West, bringing to life the rich history and enduring legacy of the Chuck Wagon.

Hazards on the Trail

Driving cattle over the various trails was by no means an easy or unassailable task. The cowboy was forced to cope with the perils of the frontier. These perils included terrible roads, rough weather, cattle stampedes, and requiring men to pass through Indian Territory to reach their destinations. In addition, the Indians encountered often demanded tributes from the cowboy as compensation for being allowed to traverse their lands. Wild West Podcast proudly presents. Hazards on the Trail Part 1: Big Blue, Firefox, and River Crossings. Make sure you stay with us after today's podcast as Mike and I discuss the unwritten rules of the cowboy on the trail.

PART SEVEN: A

Herd and Hazard: An Insight into the Challenges of Cowboy Life

In the late 19th century, cowboys faced treacherous terrains, tempestuous weather, and tumultuous cattle stampedes on the wild trails. This era's perilous tales offer a compelling insight into the life of cowboys, including their interaction with Indian territories and their survival against the harsh elements. This blog post takes you on a journey into this historical period, highlighting the dangers these cowboys faced and the courage it took for them to persevere.

The first point of discussion in this exploration is the hazards cowboys encountered on the cattle trails. The cowboys of this era had to contend with terrible roads, rough weather, cattle stampedes, and the need to pass through Indian territory to reach their destinations. Furthermore, they often had to pay tributes to the Indians they encountered as compensation for being allowed to traverse their lands. The picture painted by these cowboy tales depicts a world fraught with danger and uncertainty, yet also imbued with a sense of adventure and discovery.

Navigating rivers was another significant challenge for these cowboys. The narratives of Hiram G Craig and Jerry M Nance, who had to navigate the Washtaw River and Colorado River respectively, highlight the complexities involved in such endeavors. Cowboys had to find suitable crossing points, keeping in mind the water's depth, current speed, and the steepness of the banks. When cattle were swept away by the current, cowboys had to ride along the banks to find the lost animal, hoping it survived the ordeal.

An essential part of the cowboy life was the adherence to the 'Code of the West.' This unwritten code was crucial for their survival. It emphasized fairness, loyalty, and respect for the land. It included principles such as giving enemies a fighting chance, never stealing another man's horse, and never making threats unless they planned on backing them up. The loyalty of the cowboys to their brand was critical as it determined their survival.

In conclusion, the life of 19th-century cowboys was filled with challenges and hardships, but also adventure and camaraderie. Their survival in the harsh conditions of the wild west was a testament to their resilience and adherence to the unwritten 'Code of the West.' Their stories continue to fascinate us, offering a window into a unique period in history where men battled nature and each other to carve out their existence.

The first point of discussion in this exploration is the hazards cowboys encountered on the cattle trails. The cowboys of this era had to contend with terrible roads, rough weather, cattle stampedes, and the need to pass through Indian territory to reach their destinations. Furthermore, they often had to pay tributes to the Indians they encountered as compensation for being allowed to traverse their lands. The picture painted by these cowboy tales depicts a world fraught with danger and uncertainty, yet also imbued with a sense of adventure and discovery.

Navigating rivers was another significant challenge for these cowboys. The narratives of Hiram G Craig and Jerry M Nance, who had to navigate the Washtaw River and Colorado River respectively, highlight the complexities involved in such endeavors. Cowboys had to find suitable crossing points, keeping in mind the water's depth, current speed, and the steepness of the banks. When cattle were swept away by the current, cowboys had to ride along the banks to find the lost animal, hoping it survived the ordeal.

An essential part of the cowboy life was the adherence to the 'Code of the West.' This unwritten code was crucial for their survival. It emphasized fairness, loyalty, and respect for the land. It included principles such as giving enemies a fighting chance, never stealing another man's horse, and never making threats unless they planned on backing them up. The loyalty of the cowboys to their brand was critical as it determined their survival.

In conclusion, the life of 19th-century cowboys was filled with challenges and hardships, but also adventure and camaraderie. Their survival in the harsh conditions of the wild west was a testament to their resilience and adherence to the unwritten 'Code of the West.' Their stories continue to fascinate us, offering a window into a unique period in history where men battled nature and each other to carve out their existence.

As much as we like to romanticize cattle drives, they were more complicated than we imagined. Hours were long, food was monotonous, horses were bad, cattle were worse, and sleep was hard to come by. Yet, despite the hardships, many young men during the second half of the 19th century answered the call for trail hands. The allure of trailing thousands of cattle over wild lands and visiting far-off cattle towns like Abilene, Dodge City, and Elsworth was too much to resist. Like most adventures, the extended drive had a mix of hot sun, dust storms, thunderous rain, and treacherous river crossings, along with merriment and peril. Follow us now as we look at some cowboy tales describing the dangers of a cattle drive. While these cowboy experiences cannot give us a complete look at every threat the cowboy faces, they should paint a general picture that will help us understand the known hazards. No matter which direction the drives took, they all faced roughly the same set of perils: stampedes, river crossings, and Indian attacks.

PART SEVEN B:

From Prairie Chickens to J-Hawkers: Unraveling the Adventures of 19th Century Cowboys

The Wild West has always been synonymous with thrilling adventures, unforgiving landscapes, and the indomitable spirit of the cowboys. These hardy individuals were a breed apart, with their lives on the cattle trails filled with unpredictable dangers and the relentless test of survival. Our latest podcast episode, "Dusty Trails and Raging Stampedes: A Journey Through the Perils of 19th Century Cowboy Life", gives you a vivid glimpse into the real world of these iconic figures.

A cowboy's life in the 19th century was anything but easy. The image of freedom and heroism often associated with cowboys is far from the harsh realities they faced. Long hours, poor food, unpredictable storms, and the constant threat of stampedes were a part of their daily existence. The cowboy life was one of endurance and resilience, often with little reward at the end of the trail.

One of the most significant dangers cowboys faced was stampedes. Triggered by unusual noises, smells, or even the crackling of a dead stick, stampedes were chaotic and deadly events. During a stampede, thousands of cattle would blindly rush through the darkness, causing widespread destruction and often resulting in serious injuries or deaths of cowboys.

Beyond the danger of stampedes, cowboys also faced the risk of encounters with native tribes or J-hawkers, groups of cattle rustlers who posed as hunters. These encounters could turn a routine cattle drive into a harrowing adventure, resulting in chaos, loss of cattle, and even the death of cowboys. Such encounters further underscored the unpredictable and perilous nature of the cowboy life.

Despite these dangers, the cowboy spirit was indomitable. The excitement of the journey, the thrill of the unknown, and the camaraderie between the cowboys made the experience worthwhile. The cowboy songs that echoed in the air after a hard day's work captured the essence of their spirit and resilience, offering a soothing respite from the hardships of the trail.

In the end, the life of a 19th century cowboy was a testament to the indomitable spirit of adventure and resilience. Despite the numerous perils and hardships, these individuals rode on, driven by the lure of the open trail and the promise of a new frontier. The legacy of these cowboys continues to resonate, their tales of courage and endurance serving as a testament to the human spirit's ability to thrive against all odds.

In conclusion, the 19th century cowboy life was far from the romanticized version often depicted in popular culture. It was a life fraught with danger, hardship, and unpredictability. However, it was also a life of adventure, camaraderie, and resilience, embodying the pioneering spirit that defined the era. Join us in our podcast episode as we delve deeper into these stories, unraveling the gritty realities and unforgettable adventures of the 19th century cowboy life.

A cowboy's life in the 19th century was anything but easy. The image of freedom and heroism often associated with cowboys is far from the harsh realities they faced. Long hours, poor food, unpredictable storms, and the constant threat of stampedes were a part of their daily existence. The cowboy life was one of endurance and resilience, often with little reward at the end of the trail.

One of the most significant dangers cowboys faced was stampedes. Triggered by unusual noises, smells, or even the crackling of a dead stick, stampedes were chaotic and deadly events. During a stampede, thousands of cattle would blindly rush through the darkness, causing widespread destruction and often resulting in serious injuries or deaths of cowboys.

Beyond the danger of stampedes, cowboys also faced the risk of encounters with native tribes or J-hawkers, groups of cattle rustlers who posed as hunters. These encounters could turn a routine cattle drive into a harrowing adventure, resulting in chaos, loss of cattle, and even the death of cowboys. Such encounters further underscored the unpredictable and perilous nature of the cowboy life.

Despite these dangers, the cowboy spirit was indomitable. The excitement of the journey, the thrill of the unknown, and the camaraderie between the cowboys made the experience worthwhile. The cowboy songs that echoed in the air after a hard day's work captured the essence of their spirit and resilience, offering a soothing respite from the hardships of the trail.

In the end, the life of a 19th century cowboy was a testament to the indomitable spirit of adventure and resilience. Despite the numerous perils and hardships, these individuals rode on, driven by the lure of the open trail and the promise of a new frontier. The legacy of these cowboys continues to resonate, their tales of courage and endurance serving as a testament to the human spirit's ability to thrive against all odds.

In conclusion, the 19th century cowboy life was far from the romanticized version often depicted in popular culture. It was a life fraught with danger, hardship, and unpredictability. However, it was also a life of adventure, camaraderie, and resilience, embodying the pioneering spirit that defined the era. Join us in our podcast episode as we delve deeper into these stories, unraveling the gritty realities and unforgettable adventures of the 19th century cowboy life.